Introduction

Political organizations work day-in-and-day-out, all year round to achieve their primary goal—victory in the election.

No matter how much emphasis party leaders place on the necessity for year round programs, however, it is inevitable that political activity will reach its peak during the campaign period that culminates in Election Day.

More people are directly involved in elections than might be thought. It has been estimated that in a congressional election year, some 750,000 elective officials— ranging from U. S. Senator to municipal councilman—are chosen by the voters. Assuming that there are two candidates for each position and this is not counting third party candidates, approximately 1,500,000 people are seeking an elective office—every two years.

Candidates for major offices will have a large organization behind them; even those seeking minor offices may have several workers helping their cause. Thus, millions of people are directly involved in political campaigns as candidates or workers.

Those not so directly involved will also be alerted to the campaigns. They will attend meetings at which candidates speak; read reports of candidates’ views in the newspapers and magazines; hear political slogans repeated endlessly on the radio; see candidates’ pictures on billboards, and watch candidates on television. In recent years, thanks in part to the citizens united decision, we will also be viewing on television countless “attack” ads funded by single issue advocacy organizations.

Most Americans realize this barrage of propaganda in behalf of particular candidates, or more often opposed to the candidate on the “other side”, didn’t just happen. But they will give little thought to the organization that is behind it.

This chapter reviews the organization of a campaign. For although the goal of the campaign— to win the election—is simple, the way to achieve that goal is complex.

The election is the pay-off for a candidate or party. When you become active in politics you will sooner or later find yourself working in a campaign. Political status and influence is determined largely by one criterion—can you get votes for the ticket?

As a result, your standing within the party will depend in large measure on how much you can contribute to the success of a campaign.

Regardless of your agreement or disagreement with the party (we are talking about the two major parties) on many of its positions, in order to become truly effective, you need to choose one and through time and your effective involvement, you and others like can be a positive influence for change.

You can, of course choose to work for a party, other than the Democratic or Republican Party and their agenda may be much more reflective of your own view of how our government should work. Indeed the lessons to be learned from this course can assist you in getting third party candidates elected in local and even regional elections. Be forewarned however that the politics of America favors the two dominant parties when it comes to statewide and national elections. A few independents may make it to the U.S. Congress on occasion but Ross Perot was the last time anyone other than a Democrat or Republican made any credible run at the Presidency.

The Purpose of a Campaign

EVERY POLITICAL campaign is different in some ways from the one that preceded it. Candidates change, public opinion and issues shift. A campaign in one locality is different, too, from a campaign in another locality.

In some areas, nomination by one party is tantamount to election. In those areas, the bitterest, most hard-fought battles may take place within one party prior to the primary election. In other areas, the candidate can devote virtually all their time and attention to the general election because endorsement by a well-organized party has assured them that they will have little or no opposition in the primary.

In a farming area, the campaign will focus attention on issues that are different from those emphasized in an industrial city.

The size and structure of the campaign organization will vary from party to party and from place to place.

These obvious differences, however, should not be allowed to obscure the fact that every campaign has the same purpose— to win an election. And it must always be remembered that the only way to win an election is to get more votes at the polls than the opposition.

The organization of a political campaign is geared to that major task of getting votes.

Saints, Sinners and Saveables

A worker in a campaign is convinced of the righteousness of his or her cause.

They are convinced that their side represents “Truth, Justice and good government,” and that the only way to achieve these goals is through the election of their ticket.

As the chapter on “The Political Precinct” explains, the voters can be easily divided into three major groups—the Saints, the Sinners and the Saveables.

The Saints, quite naturally, are those on the campaign worker’s side. They are the people who are Republicans—or Democrats; have always been Republicans or Democrats; and will continue to vote for the “ticket” no matter who the candidates are.

The Sinners are comparable to the Saints—except in one important particular. They are on the other side.

The Saveables include the “independents”; those who have weak party loyalties and are willing to shift their allegiances in any campaign; and those who are completely indifferent to politics because they feel “my vote doesn’t count” or “it doesn’t make any difference which side wins.”

The size and composition of these three groups—the Saints, the Sinners, and the Saveables—shape the character of the campaign in each locality.

Concentrate on the Saints.

At first glance, it might appear that, because the Saints are already inclined to support the party’s candidates, most attention during the campaign should be focused on converting the Sinners and the Saveables. Practical politicians, however, have learned in the school of hard knocks that most attention should be given to the Saints. While it is true that these people favor the candidates, many of them will not bother to vote unless they are stimulated to action in a vigorous campaign.

Most important, they must be convinced they have a winner.

Simple mathematics will help illustrate the importance of the Saints. In the 2012 presidential election, 130,234,600 of the total voting age population of 240,092,957 in the United States actually voted. This was 54.6% of the total eligible voters. In the off-year elections of 2008 and 2010 the percentage of voting age actually voting was around 37%. In presidential election years a little less than one-half of the voting age population stays home and in off-year elections around two-thirds of the voting age population stays home.

In states where there was a presidential primary the percentage of those voting is significantly lower than those voting in the general election. In Wisconsin in the 2012 presidential primary, only 26.1% of the eligible voters cast ballots. It gets even worse for a turn out in partisan primary elections. In the 2012 partisan presidential primary in Wisconsin less than 20% of the eligible voters went to the polls.

Translate these figures into work at the county or municipal level. Suppose that there are 5000 eligible voters and only 40% (probably high) of them actually vote. This means that only 2000 votes will be cast and counted. For a majority, a candidate in that community only needs 1001 votes, slightly more than 20% of the total electorate. There are few areas in the nation where the candidate of either major party does not have the potential support of one fifth of the electorate.

At the local level even third party and Independent candidates have a chance with a well-organized campaign to win an election. Any candidate, particularly those under the wing of one of the two major political parties, has a good chance of being elected if his or her campaign creates enough enthusiasm among his or her supporters to get every one of them to the polls.

A major purpose of the campaign, therefore, is to instill so much enthusiasm among some of the supporters that they will ring the doorbells of the others, baby-sit, and carry on all the other activities that will insure that every Saint does vote.

Ed Flynn, a former Democratic political leader, said:

“It must always be remembered that the people who are going to get out the vote in the election districts are regular organization people, either Republicans or Democrats. If they are enthusiastic, these men and women get out the vote. They will see to it that every advantage is given to their ticket—such as helping those enrolled in their party to get to the polls, calling on voters before the election, distributing campaign literature, and in dozens of other ways. If they fail to show this enthusiasm, it is bad for the candidate. It is sort of passive resistance.”

In practice, of course, no campaign succeeds in getting every supporter of a candidate to the polls. Some of the lukewarm Saints defect. The second largest amount of time, money, and emphasis in the campaign, therefore, is directed at the Saveables.

In recent years both major parties have increasingly relied on television and radio advertising – all too often negative attack ads – as a replacement for the more direct method of personal contact in seeking votes for their candidate. The author has lived in very politically active communities and cannot remember of ever being personally contacted seeking a vote for a candidate. Yes, there were the Robo-calls or calls by someone doing a “survey”, but NEVER, ever a personal visit, NEVER a phone call by a neighbor or friend, and NEVER, EVER, a call by a candidate. Would my vote have been influenced by a personal appeal for my vote, the answer is yes.

Party members vote for party candidates

The voter demographics from the 2012 presidential election clearly establish the fact that those identifying themselves as either Democrats or Republicans almost always voted for their party’s candidate. Clearly the battle is for the independent vote!

| Obama | Romney | Others | Total % | |

| Democrats | 92% | 7% | 1% | 38% |

| Republicans | 6 % | 93% | 1% | 32% |

| independents | 45% | 50% | 5% | 29% |

The Republican Party is generally considered to be a “conservative” party and the Democrats are considered a “liberal” party. In the 2012 presidential election the voting patterns of those labeling themselves as “conservative” or “liberal” tended to follow, but with more cross-over voting, the patterns of those identified as Democrats or Republicans.

| Obama | Romney | Others | Total % | |

| Liberals | 86% | 11% | 3% | 25% |

| Conservatives | 17% | 82% | 1% | 35% |

| Moderates | 56% | 41% | 3% | 40% |

Fortunately much of the effort directed toward getting the hard-core organization enthusiastic and convincing its members that they can win the election also helps convert the Saveables. Some independents will “jump on the bandwagon” if they are convinced it is really rolling; others can be persuaded to support the candidate through publicity, advertising, speeches—or even a simple handshake.

In addition, special appeals are frequently used to reach those Savables who are members of certain groups, such as lawyers, doctors, farmers, labor, and veterans.

Often, such loosely-knit organizations are called “letterhead clubs,” because appeals for support of a candidate are sent out on the “club letterhead” that carries the names of the sponsors. They are not of course, true clubs; only campaign devices to appeal to special groups of Savables.

The same type of appeal is carried a step further in the “citizens for Whoosit” clubs that are even more highly developed campaign organizations outside the party fold.

“Citizens for Whoosit” clubs offer a method for obtaining campaign workers who will back an individual but shy away from affiliation with a party. They also provide a means of appealing to independent voters and of raising money that would be unavailable, otherwise.

The inherent weakness of such splinter “clubs” or “citizens for ‘Whoosit” are sprinkled throughout the history of American politics. A major historical example is the Associated Willkie clubs of America formed in 1940. The Associated Willkie clubs so dispirited the regular Republican organization that it spelled disaster for both the organized party and the amateurs. Coming into the 1940 Presidential elections President Roosevelt’s popularity was in decline and for a time Willkie was favored to win the election. It is generally thought that the activities of the Associated Willkie clubs were a significant factor in Willkie’s loss in the general election. In the 1964 Presidential election Barry Goldwater’s campaign was hampered by the support of the John Birch Society whose far-right anti-communist agenda cooled the support of the regular Republican base and gave the Johnson campaign multiple targets of opportunity.

A more recent development is the Tea Party movement within the Republican Party. It is generally considered that the Republicans lost a chance to take control the U.S. Senate in 2010 and again in 2012 due the activity of the Tea Party (as effective as it may have been in the primaries) in putting candidates for the U.S. Senate on several state ballots where their far right positions (and sometimes highly controversial statements) turned almost sure Republican victory into a seat for the Democrats. Whether or not the Tea Party goals are a good or a bad thing is not the point. The point is that in a country (ours) that has been a two party system, whether clubs or minority movements within one of the established parties, their activity usually spells political harm for the dominent parties.

Many political observers say that the undoubted ability of these “independent” entities to influence voters and to raise money is offset by an inherent weakness. Since they are outside the regular party organization, the chances of them being around for the next election cycle, particularly if the candidate they were backing lost in the election, is small. In the presidential election of 2008 many student organizations supported Obama and even though he won the presidential election many failed to support his 2012 campaign, at least with the levels of support he enjoyed in 2008.

Least attention in a campaign is devoted to the Sinners. Converting them is so difficult that it is generally an uneconomical use of time. The best that can be hoped for is that they will become so discouraged that they will not vote or will slacken their efforts to get others to vote. Most politicians try to discourage the opposition workers by issuing glowing victory predictions during the campaign, and by similar techniques.

Organization is the Key

It is not by accident that the dominant political faction in many districts is called “the organization.” Successful political campaigns are always organized campaigns. Every campaign manual stresses the importance of organization. Here is a typical example from a major party campaign manual:

“Organization is the first requirement for victory, for without effective political organization it is difficult to sell the Party. The art of successful campaign management demands a thorough understanding of the principles of political organization.”

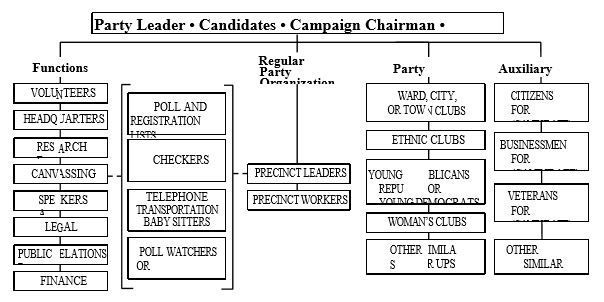

A Typical Campaign Organization

The organization of a national campaign will be different from that of a campaign for a local school board. In some campaigns, the county chairman and county political organization may run the whole show with an iron hand; in other cases, an individual candidate may set up elaborate machinery because the local party machinery is virtually non- existent. Or, perhaps, the candidate may set up a small organization and rely on the county organization for supplemental help.

Candidates who are thoroughly versed in the art of politics may make all major decisions on strategy; inexperienced candidates may turn all these decisions over to a politically- experienced manager.

Policy Group

The precise organization of the top echelon in a campaign will vary with the campaign and the personalities involved.

In some cases, the party leader will dominate the group; in other cases, an experienced candidate may make all final decisions. A campaign manager may merely carry out the orders – or may mastermind the entire campaign

Despite all these differences, it is still possible to draw up a composite organizational chart that is valuable for purposes of illustration. Basic problems are the same in every campaign—the same principles apply. In the final analysis, certain jobs must be done if the campaign is to be waged as effectively as possible. A good campaign organization is one set up to do these jobs.

Because they know specific tasks must be accomplished in every campaign, party leaders and candidates can start shaping up their organizations long before the election by selecting the men and women who will fill key positions.

The Campaign Manager

Almost every practical politician agrees that a candidate should not plan and conduct their own campaign. The physical strain of an active speaking tour may prevent them from devoting adequate time to planning strategy.

Equally important a candidate may not be familiar with the actual mechanics of a campaign.

Most politicians agree, too, that the candidate should be “insulated” as much as possible from the bad news and criticism that may crop up in any campaign. Anything that lessens their confidence and decreases their enthusiasm hurts their effectiveness. For these and other reasons, a campaign manager is generally appointed.

The one most important qualification of a campaign manager is that they be a “professional.” This does not mean professional in the sense of being paid, but rather means experienced, skilled, and resourceful.

In addition, the campaign manager must have a quality that might be called “equilibrium.” Their temperament should be such that they can “roll with the punches,” and be able to deal with emergencies quickly and decisively. Certainly, they should not be the type of person who is likely to “panic” when faced with harassment or problems.

The campaign manager must have the ability to work in the background. Anonymity is their byword. In fact, one of their jobs will be to see that other workers and the candidate get the publicity.

A brief outline of a campaign manager’s responsibilities is presented this way in a Republican campaign manual:

“The candidate is the campaign’s front man; and the campaign manager is in effect its business manager. He or she has the overall responsibility of administering its ideas and affairs and of taking the mechanics of the campaign organization and operation off the hands of the candidate. This leaves the candidate free for speeches and top-level thinking on policy and strategy problems. The two must maintain the closest relationship and keep their thinking allied together at all times.”

“In case there should be any disagreement which cannot be worked out through consultation, final decision should be made by the candidate.

“The manager’s role is not to do the work by themselves, but to get other people to do it, to make sure that they do it. And to make sure that they do it efficiently.”

Another most important qualification of a campaign manager is that they be a good administrator. A campaign consists of the weaving together of a multitude of different threads—literature, publicity, speeches, advertising programs, voters’ canvassing, and so on. The skillful campaign manager must not only know what these details are, but they must know how to select the men and women who will head these various projects and programs— and get them accomplished.

They must know how to weed out those who are merely seeking personal publicity, and the emotionally unstable. They must concentrate instead on finding competent people who will perform their assignments efficiently. Sometimes, they may have to persuade people outside the regular organization to perform a special job the campaign manager knows they are well equipped to handle.

To quote again from a Republican campaign manual:

“Many campaigns are run with the loosest and most haphazard campaign structure imaginable, without either clear lines of authority or clear understanding of responsibility. But such haphazard organization and structure bring only haphazard results.”

The first job of every campaign manager is to set up a campaign organization with a clear structure. This simply means, as a practical matter, that every function should be delegated clearly and specifically to someone, preferably in writing, with a clear line of authority and a perfectly clear understanding of responsibility on the part of the person who is to carry out the particular program.

Nothing causes so much trouble as a misunderstanding, and because of the fluid and dynamic character of a political campaign, especial care must be taken to prevent misunderstandings in this fast-moving field. The need for clarity increases with the scope of the campaign.

Where possible, the campaign manager should reserve no administrative or operational responsibilities for them, but should delegate them all.

When a new and workable idea appears on the horizon, they should put somebody in charge of it as a new program immediately, reserving for themselves the basic role of coordinating, troubleshooting, and developing new ideas. They will be busy enough with these duties. In addition, they should try to delegate as much of their administrative and clerical responsibilities as possible. Otherwise they will find themselves bogged down in detail, behind in their work, and with no opportunity to do the top-thinking at top level which is the basic job of the campaign manager.

In short, the campaign manager should have the knowledge and skill of the “professional” politician; the administrative ability to delegate authority and at the same time to maintain control; and the leadership to inspire a group of volunteers to work hard without friction.

Training Schools for Workers

Within the last few years, state and national political organizations appear to have decreased their efforts to provide systematic training of political workers through schools of politics. It seems that the party emphasis has shifted to using the massive amounts of money that now flows into the political process rather than concentrating on recruiting and training political workers. There appears to be little available through either the Democratic or Republican parties for people who “might be interested” in getting involved in politics or for those who just might want an education in how to be a better citizen.

Both national parties do provide programs in campaign management for those seriously interested but local parties do not seem to provide much support. Interested parties should check the web sites of the national Federation of Republican Women or the Democratic campaign management Program. There are also fee-based private organizations that provide services to both parties. Check the website of Aristotle.com.

Campaign Activities

Practical politicians have identified specific functions for which specific responsibility must be assigned in every political campaign.

A headquarters must be set up and operated, research must be done, speakers must be provided for various types of meetings, voters must be canvassed and gotten to the polls, legal work must be handled, the many aspects of public relations must be performed, and funds must be raised for the expenses of the campaign.

The responsibility for performing each of these functions is assigned to a committee. Actually, many of these will be “one person committees,” since more than one is not necessary to do the job—or, more than one may not be available.

Nevertheless, the word committee is used to describe the person or group which is assigned each function, simply because it is the best word available, and the one most commonly used.

Headquarters

Every political campaign should have a headquarters. In small towns, this headquarters is located, if possible, in a vacant store on the main street. In strictly local campaigns “headquarters” may end up being the candidate’s kitchen table. Having a designated headquarters that is a public location is not only convenient, but permits continuous advertising by placing a banner across the front, or possibly even across the street. In larger cities, the campaign headquarters is frequently set up in a suite of offices—that can be expanded as necessary.

The job of running the headquarters generally falls to the headquarters secretary, who is frequently a full-time paid employee. They see to it that office supplies are adequate, that appropriate officials have keys to the headquarters, and that a schedule of meetings being held in the headquarters is kept.

They also handle much of the dictation and word processing for the campaign chairperson, may keep the treasurer’s books and do the routine purchasing. Many campaign headquarters make it a practice to keep hot coffee and soft drinks available for the workers and various people who drop in. Taking care of the refreshments is also a responsibility of the headquarters secretary.

Volunteers Chairman

Sometimes, the headquarters secretary doubles as chairman of volunteers. More often, another person who can work almost full time is appointed to head up the volunteers operation.

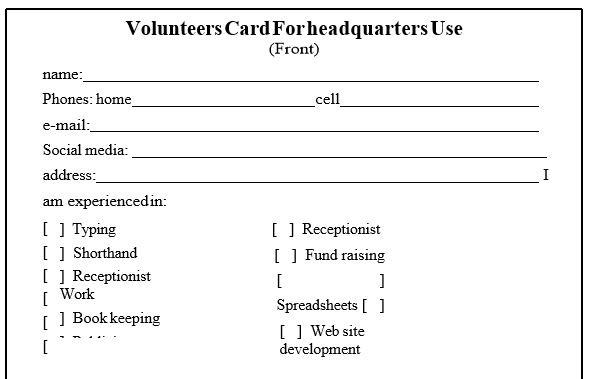

Since political organizations rely almost entirely on volunteer help to perform all the different jobs necessary to a political campaign, the responsibilities of the volunteers chairman are very heavy. Generally, their responsibilities cover four areas—recruiting; assigning jobs; training; and helping with non-headquarters staffing.

Recruiting. The first responsibility is recruiting a large enough pool of volunteer workers with the qualifications necessary to do the different types of jobs required. Many volunteers will just turn up at headquarters and sign a card.

Political clubs will generally submit a list of their members who can be called on for help. The volunteers chair person has to use their own initiative in finding additional volunteers they may need.

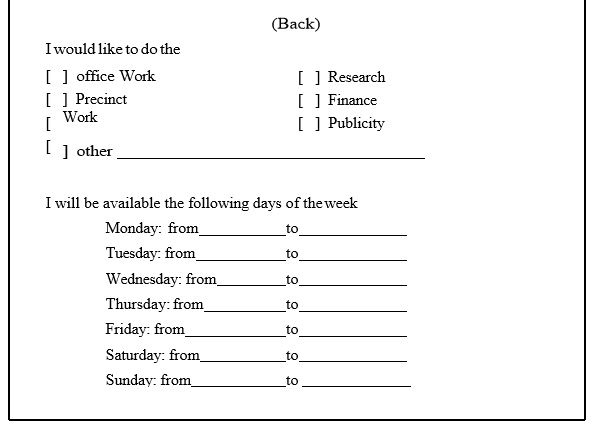

Assigning Jobs. Their next job is determining what each volunteer wants to do—and can do. Generally they will use some form of data management system to keep a searchable record of each volunteer’s abilities and the times that they may be available. The volunteers chairman then use their files to make out a schedule of assignments for receptionists, typists and other regularly scheduled personnel. They also develop a ready list of people for emergency calls.

Few volunteers are completely unusable. It is up to the chairman not only to have them available when needed, but also to see to it that everybody who wants to help has an opportunity to do so. Nothing is more discouraging than for a person to volunteer his or her services and never be called on to help. When this happens the word spreads fast that the party is not interested in having people help or, worse yet, the party is disorganized and lacks focus.

The volunteer card lists the last name first for ease in alphabetizing. The information from the cards is inputted into a data management program. There are many fee based organizations that provide comprehensive data management systems, such as Aristotle, to assist in fundraising, voter data analysis, compliance reporting, get out the vote campaigns and other political management tools. If all the organization wants to do is keep track of the volunteer’s abilities, their work preferences and their availability the management tools that come with most wording processing programs will probably be adequate.

Training. The volunteers chairman also has a responsibility to train headquarters personnel in how to take care of visitors, telephone answering technique, the filing system, and the other basic information they need to work in the headquarters.

Non-headquarters Staffing. The volunteers chair should also be on the

lookout for potential precinct workers and other non-headquarters types of volunteers. After referring these people to precinct leaders or other chairmen, they should follow up to make sure the volunteer actually gets in touch with the precinct leader or committee chairman.

The volunteers chairman needs several qualities. They must have great tact and diplomacy so that each volunteer feels his or her services is valued. They must be a good judge of people so they can fit each person into the proper job. They should be a leader capable of motivating their volunteers to work above and beyond the call of duty. They must be resourceful and not given to panic, because half the requests they receive for volunteer help will be on a crash basis.

Research Committee

In practice, the scope of the work done by the research committee generally reflects the size of the campaign. The national committees of both parties are constantly analyzing issues and the party’s prospects in various sections of the country. Most state central committees, too, have sections for research. At the county and municipal level, the research committee may be one of the less active groups—although a well-organized research committee can perform a tremendously vital service in any campaign.

One of the committee’s major jobs is to prepare material that the campaign speakers can use effectively. The speeches and the voting record of the opposition candidate can be combed for material that will be helpful in the campaign. Background material on issues and opponents can be compiled by the research committee and made available to the candidate and to other speakers.

In addition, invaluable help can be provided to the campaign manager and their candidate in the development of their campaign strategy.

If funds are available, polling data may be contracted for and polling results integrated into the research assignments.

Research can find the answers to questions such as these: What is the total number of voters in the district? How is the population broken down by ward and precinct? What was the vote by ward and precinct in the last election? Are there concentrations of ethnic groups in certain precincts? Where will concentrated work get us the most votes? Will ads and positions designed to gain votes from a specific ethnic or interest group cause the campaign to loss the support of other groups?

The answers to such questions—which should be available prior to the planning of the campaign—are of inestimable value. In some cases, of course, the professional old-timers through long study of the politics of their area will know most of the answers—but established views can always be re-examined.

Since the primary purpose of the campaign is to insure that voters on your side get to the polls, it is essential that the campaign manager know which areas and which groups are worth all-out efforts and which are not.

If there is a large ethnic group in the district, special attention may be given it. Or efforts can be made to enlist the support of substantial groups by appeals to their leadership—since politics revolves around people who influence others.

In recent years, increasing interest has been evidenced by candidates and parties relying heavily on the use of public opinion polls and focus groups. In many cases the candidate’s positions are tailored to reflect the opinion poll and focus group results. Unfortunately the reliance on polls and focus groups may lead to the voters being told what the politician doing the telling thinks the voter wants to hear rather than what they need to hear.

In most areas, the research committee can conduct its own public opinion polls, in addition to collecting information on all types of voters’ statistics. A word of caution: designing questions, selection of samples, interview techniques and interpretation of findings require experience. Professional help in conducting polls is advisable. A quick search on the internet will find many local and national polling organizations. State party organizations should be consulted for recommendations.

Speakers Committee Today political programs must compete with all kinds of entertainment for public attention. Under the impact of radio and particularly television political oratory has changed. Political speeches are often much shorter they once were. In most cases, they do not include as much flowery verbiage but speech-making is still very much a part of the political scene.

During a campaign, requests that the candidate speak before this group or that club will flow into campaign headquarters. Obviously, the candidate cannot accept all invitations to speak. The campaign manager and the candidate, therefore, select those that they believe will pay off in the most votes. In selecting the speaking engagements that the candidate will accept, the candidate and his manager will keep in mind the major goal of the campaign mentioned earlier – that is to get those people who support him to the polls. This means, for practical purposes, that a Republican candidate would spend little, or no, time in a precinct that had a long history of large Democratic majorities. He or she should recognize that the few votes they might change in that precinct would not justify the use of much of their limited time. They can devote their energy more constructively to making sure that the voters who are at least sympathetic to their cause are inspired to increase their efforts to elect them and to support them at the polls.

Some of the candidate’s appearances are almost mandatory, of course.

They will probably show up at any gathering which includes a large number of the party faithful. They will always try to appear before veterans groups, labor meetings, religious organizations, chambers of commerce and other important, well-organized clubs or associations. In many communities, nonpartisan organizations such as the League of Women Voters will hold a rally to which all candidates are invited. A candidate generally will make a point of attending such meetings since their absence would probably be misinterpreted. On the other hand if one candidate is widely known, they may find it unwise to give their lesser known opponent the publicity that comes with appearing on the same program. Or if the candidate is a poor debater they would probably be wise to avoid any program that is essentially a debate.

Candidates may be forced, by circumstance, to appear before groups that have a history of voting for the opposite party. These circumstances may be negative ads put out by the opposition that falsely portrays the candidate as being pro or anti a position that is important to the group. Other situations will arise in any campaign that may require the candidate and their campaign manager to weigh the benefits of appearing before a potentially hostile group where few votes can be obtained. If the candidate is quick to lose their temper or is a poor speaker before a hostile or non-responsive group it is probably better to stay home.

A well-organized speakers committee will have available a “stable” of able speakers to fill requests for a speaker at the meetings which the candidate cannot, or does not want to, accept.

The committee will also stimulate requests for speakers and take the initiative in finding spots for speakers at local luncheons, dinners and meetings sponsored by influential clubs and organizations. Many program chairmen will welcome a speaker on a political subject during a campaign period.

Like all other groups participating in the campaign, the speakers committee will be successful in direct proportion to the knowledge and skill possessed by the leadership and in its ability to work harmoniously with others. Naturally, its efforts require coordination with other committees that are working on the campaign.

The speakers committee works, for example, with the research committee in developing material that will be most useful and effective in campaign speeches. It also works with the public relations committee in ensuring that the speakers and their speeches receive wide publicity, and in handling the distribution of effective pamphlets or other material at meetings.

The speakers committee must have a clear understanding of the political situation in the area. Its chairperson should know the type of appeal most likely to influence a legion meeting and what type will appeal to the annual dinner of a professional society. Knowing what subjects to avoid is just as important.

Solving the many and varied problems of a campaign requires the ability of a successful diplomat. In almost every campaign there will be volunteer speakers who will do more harm than good if they are allowed to speak as “official” party representatives. Easing these people into other jobs without hurt feelings may not be easy, but it is essential. The success or failure of most meetings is determined by the speaker. Inept and inadequate speakers are worse than no speaker at all, since they alienate some votes and fail to attract others.

Because of the importance of speakers, some speakers committees may operate a training school at the beginning of the campaign to develop the skills of new speakers and to apprise those who wish to participate in this phase of the campaign. The state party organization may offer some training for potential speakers.

The Small informal gathering: The subject of speakers and meetings brings up a relatively recent development that has changed campaigning in some areas—the small, info– gathering. It was said, for example, that former President Jack Kennedy “literally drank his way in tea into the Senate,” as he met thousands of voters at a series of informal tea parties conducted by his mother and her friends.

The idea is simple. A housewife or maybe a stay at home dad in the neighborhood invites as many friends as possible in for a cup of tea or coffee, and to meet the candidate. There is no formal program, but those in attendance are given an opportunity to shake the hand of the candidate and to chat briefly with him or her.

The success of such meeting in swaying voters is not surprising. The candidate immediately becomes a “friend” of the voter. Human nature, being what it is, there are few people who will not find the opportunity later to mention to others that “Mr. Candidate told me the other day . . ..’ or to say casually “When I was talking to Mr. Candidate the other day at the Browns’ house “. .

If the candidate has a pleasing personality, as most of them do or they wouldn’t be candidates, each person in attendance immediately becomes a center of influence, spreading the “good word” to all of their friends.

Ronald Reagan used a version of this “small informal group” approach in mounting support for his health care program that was supported by the American Medical Association. Regan rightly assumed that letters from women in support of Reagan’s position would have more impact on Congress than letters from doctors. A massive effort was made to enlist Republican women’s club members to invite their friends to listen to a taped address by Reagan. Reagan attributed these programs to having a great impact in getting his program passed.

The development of the informal social hour as a campaign technique is, of course, just an extension of the practice that has long been followed by candidates of appearing briefly at all types of public functions, state and county fairs, picnics, and even funerals and weddings. Candidates in rural areas have long recognized the importance of attending meetings of farmers’ organizations and livestock sales.

Long time politician, Jim Farley said “There is no substitute for the personal touch and there never will be, unless the Lord starts to make human beings different than the way he makes them now.”

Practical politicians have learned it is useful to have a “buffer team” to accompany the candidate at these small informal gatherings as well as at larger meetings. The “buffer team” sees that all those in attendance have a chance to meet the candidate, prevents one or two people from monopolizing their time, answers phone calls, and gets the candidate out of the meeting in time to make his or her next appointment.

Public Relation Committee In an ideal campaign, a candidate would shake the hand of every potential voter. Obviously, that is impossible. And the more heavily populated the area, the less practical it becomes. As a result, a political campaign must rely on other indirect ways of reaching the voters.

Campaign literature—pamphlets, throwaways, posters—will help reach many voters. Paid advertisements can be placed in newspapers and presented on television and radio. In addition, all of the mass media of communication are ready to present information about the candidate—whenever they consider-the information newsworthy.

The use of social media has greatly expanded the outreach ability of the Public Relations committees. Anyone interested in the effective use of internet and social media as both a campaign and a fundraising tool should consult one or more of the analysis – both on the internet and in book form – of the 2008 Obama campaign.

In some cases a subcommittee handles the paid advertising of all kinds, including outdoor billboards. Another subcommittee handles the preparation and distribution of special literature such as posters and leaflets.

Sometimes the publicity and advertising functions of a campaign are assigned on contract to professional publicity, advertising, or public relations firms. Whatever system is used, however, the public relations director must coordinate publicity. They should be consulted and their ideas utilized by everyone involved in the campaign.

A good public relations director will, of course, know the mechanics of writing press releases. They will know how to start the copy several inches down on the first page, to have it double—or triple—spaced, to make sure that names are spelled correctly, that facts are accurate. They will know that they should answer “Who, What, Where, When and Why.”

But, it is even more important that they be thoroughly familiar with all the publicity outlets—the small weekly newspapers as well as the large dailies and the radio and television news commentators. They should know deadline requirements, be friendly with editors and commentators, and know the type of material that appeals to each of them.

A good public relations director, in handling publicity, is much more than an expert on mechanical details. They must have a news “sense” and recognize when to act and how. A good example of effective publicity action was the reaction of the committee for the election of President Obama after the release of the secretly recorded comments of Mitt Romney commenting on the 47% that would never vote for a Republican.

However, a public relations director is limited somewhat in creating “news.” in the final analysis, his or her job is to publicize the news” that is made by the candidates and by party activities.

Advertising: For the public relations director, communications media have two uses—to carry free publicity and to carry paid advertising.

A newspaper, for example, may carry in its news columns pictures of a candidate, stories about meetings, and other items that the editors consider of public interest. A radio or TV station will also report news and present panel discussions or similar programs as a public service.

At the same time, of course, newspapers, TV and radio stations are in the business of selling advertising space or time.

Although the alert public relations director attempts to obtain all the free publicity he or she can, they will also plan to spend some money for paid political advertising.

When it appears as paid advertising, a message can be presented in the form in which the public relations director wants it to appear, rather than as an editor or reporter— possibly unfriendly—would like it to appear.

Additionally, many publications expect to receive political advertising during a campaign. Very often advertising is left until the last minute. However, contracting for space early and delivering copy well in advance of deadlines eases the job of the newspaper in preparing layout and often results in better position for the ads as well as better cooperation from all concerned in making the ad more effective.

Many questions arise in the advertising campaign: how much money should be spent on newspaper advertising? … on radio? . . . on television? . . . on billboards” . . . on leaflets and brochures? Should ads be full-page? … or smaller. .

Should a television program be used for a 15-minute speech, or a spot announcement … should the ad point out the “faults” of the opponent – go negative – or emphasize the sterling qualification of the candidate? Will any television viewer ever watch any ad that runs more than 60 seconds?

These and similar questions for specific campaigns and specific conditions in any area can best be answered with the help of skilled advertising people—many of whom participate in campaigns, either as paid consultants or as volunteers. It is useful to remember, too, that use of an advertising agency in the preparation and placement of advertising generally costs the advertiser nothing—because it is standard practice for the agency to collect its fee in the form of a discount from the media in which the advertising is placed. If the account is small, however, there may be a service fee.

Professional help should be used as much as possible in all phases of the publicity and advertising program, but here are some general observations about the use of television and radio offered by practical politicians.

Television: as noted earlier, from a candidate’s standpoint, there are two major types of television programs—those that are free and those he pays for. The free type might be sponsored as a public service by the station or sponsored by an advertiser. A forum, in which candidates are interviewed by a panel of news men, or others, is a good example of this type of program. Decisions as to the candidate’s appearance on programs of this nature will be determined largely by the nature of the program, the candidate’s schedule, the character of the sponsoring organization, and the ability of the candidate to appear favorably in the format of the program. The candidate’s appearance before the harsh television lights may also have impact on a decision to participate. Many will remember the television debates of John Kennedy and Richard Nixon where most observers thought Nixon won the debates on debating skills but lost due to his appearance on the television screen.

More serious questions arise over the decision as to whether television time should be purchased to present candidates.

There is no question that television has introduced the most important new element into political campaigns.

Candidates can be seen by many more people than formerly. Those who have a good television personality can make it pay great dividends. Despite the high cost of programming—television enables the user to reach large audiences at small per capita cost.

The explosive growth of cable Television channels coupled with the decline in market share of the legacy networks of NBC, ABC and CBS has made television ad buying extremely challenging. Cable channel programs directed toward specific ethnic and demographic groups do allow the targeting of ads. But there will always be a finite amount of money and an overwhelming number of choices.

Unfortunately in the last few years much of the campaign funds available for television advertising is directed toward the production of attack ads, often without even suggesting that the voters support a candidate, that “attack” some aspect of the opponents past voting history, their character or even their personal life or in defending against or countering the attack ads of the opponent.

There seems to be a general agreement that certain subjects are always fair game such as:

Talking one way and voting another.

Not paying taxes

Accepting campaign contributions from special interests

current drug or alcohol abuse

Their past voting record

More and more barriers are being breached as to what of the opponents personal life is subject to attack but there are still some that a majority of people believe are off limits:

Lack of military service

Past personal financial problems

Actions of a candidate’s family

Past drug or alcohol problems.

According to the Huffington Post and citing an analysis by the Wesleyan Media Project, in the 2012 presidential election by May of 2012, around 70% of the ads run on television were negative ads. As compared to the same period in the 2008 presidential election when negative ads were a little over 9%. Of particular interest was the fact that over 60% of those ads were funded and sponsored by groups outside the campaign committees for either of the major presidential candidates.

Research on the effectiveness of “negative ads” is all over the map. Some research supports a conclusion that the candidate that has the most effective negative or attack ads usually win the election while other research supports the opposite conclusion. An excellent review of the competing research is contained in “The Effectiveness of Negative Political Advertisements: a Meta-analytic Revie” in the American Political Science Review, Volume 92, number 4, December 1999. Apparently campaign managers and Political action committees don’t read the research literature or are afraid to avoid the “mud-slinging” because there appears to be no end to the predominance of the negative political ads. Many high priced political consultants pride themselves on their ability to craft harsh, sometimes dishonest and false, negative advertising and other materials for the all too eager candidate to use against their opponents.

Radio: many of the comments on the use of television apply to radio. From the political standpoint the emergence and dominance of television has not killed radio. Smart politicians recognize that radio offers many advantages in terms of coverage and economy. Millions of people listen to car radios while driving to and from work; many housewives and stay at home dads listen to the radio while doing their household chores. In radio, as in television, “spot announcements” are widely used.

Billboards: Billboard advertising provides another means of publicizing a candidate.

The use of billboards enables a picture of a candidate, his name, and the office for which he is running to be prominently displayed; thereby fostering in the public’s mind an association between a face, a name, and a job.

Many campaigns use billboard advertising effectively.

Literature: no campaign is going to be so foolish as to spend all of its money on television and radio ads and forget the fact that printed material still has a significant place in any effective campaign. Professionally prepared brochures and yard signs are an important part of any well run campaign. The preparation of effective literature and its efficient and economical distribution are big tasks in a political campaign. The best printed material is of little value unless it reaches the voters. A wide variety of approaches are used in the distribution of all literature to make sure that it reaches as many different people as possible.

Literature is sometimes mailed to every potential voter in the campaign area but this can get to be expensive and the cost per voter could run, depending on the quality of the printed material, to over $2.00 per voter. In a well-organized precinct the brochures could be delivered by hand by precinct workers. Often times printed material containing a sample marked ballot is passed out near the polls on Election Day.

Special mailing pieces are often prepared for special non-party groups such as lawyers, doctors and other specific groups. If possible this material is sent out under the letterhead or signature of a respected member, or members, of the group rather than coming from campaign headquarters.

Notes on Use of Mass Media: Frequently, those preparing material for dissemination through mass media, such as publications, radio, TV, newspapers, etc., aim it entirely at the hostile and undecided. Some authorities believe that material in mass media has little direct effect on the undecided voter. They are not very interested; are bombarded with opposing claims, and t hey make their decision at the last minute.

The decision of this type of voter, these authorities say, will probably be determined largely on the basis of personal, face-to-face contact. Therefore, material carried in mass media will be effective to the extent that it impresses the party faithful in favor of their own candidate and against the opposition—and can be used by these faithful in talking to their friends and neighbors.

According to this view, the primary value of mass media is as a means of “passing the ammunition” to the front-line troops. Undoubtedly mass media make some impression on the individual voter, but the wise campaign manager will not fail to see that they are employed with an eye to this second kind of usefulness as well.

Legal Committee In small campaigns, the legal committee may merely be one individual. But every campaign requires legal services. These services are generally provided by volunteer lawyers who are experts on campaign and election law.

These experts can perform a dual function. They can insure that the party’s candidates comply with all the legal requirements for filing nominating petitions. Present legal restrictions on campaign expenditures and the necessity for filing reports on them make the services of an expert in these fields particularly helpful. At the same time they are protecting the interests of their own candidates, the campaign’s lawyers can be on the alert to insure that the opposition is complying with the law, and to advise on how any legal mistake by the opposing candidate may be exploited.

For example, both parties had large teams of attorneys mobilized within hours of the closing of the polls in Florida in 2000 as soon as the initial results of the “too close to call” election results became known.

The legal committee can perform an important and most useful service by preparing a manual or conducting a school for precinct workers who will be charged with the responsibility for challenging voters or watching the vote count on Election Day. (See “Election Day,” at the end of this chapter)

Canvassing Committee The primary objective of the canvassing committee is simple—to get all potential voters on its side registered, and then to get them to the polls on Election Day.

As the chapter on “The Political Precinct” explains, the task of canvassing voters to determine their political inclinations, getting those on your side to register, and then getting them to the polls must be decentralized to the precinct or ward level.

A canvassing committee at campaign headquarters is necessary, however, to coordinate and supervise the entire operation. It can check the organization of each precinct, hold schools for those who are doing the actual front-line work, and organize task forces to conduct canvassing operations in precincts in which the party is not well organized.

A canvassing committee can furnish maps of each precinct to precinct captains. With the help of the research committee, it can identify the areas that deserve large, intensive drives, and areas where less attention is needed.

Occasionally, a smart canvassing committee chairman will get a large group of volunteers and prepare a listing of names, addresses, and telephone numbers of the party’s registered voters in each precinct. These are then turned over to the appropriate precinct leaders, saving them days of preparation—and making sure this job is done in precincts with poor or no leadership.

On Election Day, the canvassing committee can assume responsibility for a variety of chores, including:

1. Ensuring that necessary workers are assigned to each of the polling places— and to check to see that they are actually on the job. If for some reason they fail to appear, the canvassing committee should have adequately-prepared replacements.

2. Checking the polling places early to see how the votes are coming in—say between 10:00 a.m. and noon. If voters for the party seem to be slow in appearing at the polls, the precincts should be notified to redouble their efforts. In many areas, it is a definite campaign tactic to slow down voting late in the day in the hope that voters of the other party who expect to vote on their way home from work will decide not to when they see a waiting line at the polls.

3. Providing proper credentials for party poll-watchers.

Special Services Committee During a political campaign, a candidate and his party may receive many requests for special services, as well as much free advice on how to run the campaign, tips on what the opposition is doing, and so on.

Political organizations are built to some extent by special favors they are able to perform for the voters.

The precinct leader, of course, will handle most such cases, but there are always some occasions in which a troubleshooter for the party can win votes by working on requests that cannot be handled by the precinct leader.

The special services unit can also perform a useful service in screening all the advice that pours into headquarters.

Obvious crackpots can be tactfully thanked and gotten rid of without burdening the leaders with the job. Worthwhile suggestions can be passed on to the appropriate committees or leaders.

Some politicians recommend that the chairman of the special services committee be given an important title such as “general manager” in order to deal more satisfactorily with the people who come to headquarters with fire in their eyes, demanding to see “the man in charge.”

Financing the Campaign Two major problems are connected with financing a political campaign—raising the money and controlling its expenditure. The money-raising function is the responsibility of the finance committee; expenditures are controlled by the treasurer in consultation with the campaign manager.

Finance Committee The money-raising committee of a campaign is frequently set up in an organizational unit that is independent of the candidate. Politicians say that several advantages accrue to the candidate under procedures that prevent him from knowing any more than is absolutely necessary about the campaign’s financial affairs.

For example, if questions should arise about the source of contributions or practices that have incurred resentment, the candidate can disclaim all knowledge of the practices and assure the voters that they had no knowledge about the donor. In instances where funding sources become a serious campaign liability it may be necessary to return the funds and, in extreme cases, someone on the finance committee may have to “fall on his sword “ and resign.

The enactment of legislation that requires financial reports for campaign receipts and expenditures has undoubtedly speeded the tendency to divorce the candidate from the finances.

Waging a campaign today costs large stuns of money, and a variety of methods have been developed to raise the necessary amounts. Because of the subject of fund raising for a campaign and the relationships with outside sources of advertising dollars is so complex this book only goes into a basic outline. Numerous sources of information are available by a Google search and of course from engaging the services of a professional fund raiser.

The most effective method is the personal solicitation of individuals. Letter campaigns, although not as satisfactory as other methods, are used.

$100 to $1000-per- plate dinners have as their primary purpose the raising of money for the party. This device has proved to be very successful in raising funds, when properly handled.

In addition to the members of the general public who can be persuaded to contribute, political campaigns may also rely on other sources of income. For example, it is generally expected that non-civil-service jobholders will contribute to the party. There are as many ways of raising campaign funds as there are imaginative finance chairmen. The finance committee will be aware that the Citizens United decision has opened the floodgates to vast sums of money that come from interest groups and wealthy individuals. The committee should use all reasonable efforts and exploit all contacts to take advantage of the funds that now have the potential to flow into even local elections in certain circumstances.

Legal Considerations: Many state laws place limitations on the solicitation of political contribution or on the disclosure of the source. These laws differ in the various states and the finance committee should seek information from the Secretary of State’s office on what restrictions exist in their state. If in doubt a legal opinion from an attorney familiar with state campaign financing laws should be obtained. Although the Citizens United decision has opened the floodgates for almost unlimited funds from corporations and wealthy individuals there are still some limitations as to how these funds can be used so expert legal advice should be sought if there are any questions.

Much in the area of political fund raising has changed since the U.S. Supreme Court decision in the Citizens United case. The ability of individual citizens and corporations to contribute virtually unlimited funds directly to candidates or indirectly through Political action committees (PAC’s) is currently unchecked. Many complain bitterly about Citizens United, initially more Democrats complaining than Republicans since the Republicans were quicker to take advantage of the Citizens United decision, but the truth is that all the Citizens United decision did was to make it easier for wealthy individuals and corporation to assert their influence on elections. Only the uninformed would assume that the wealthy first got influence with the Citizens decision.

Prior to the Citizens United decision wealthy individuals and corporations had to work a little harder to get the results they wanted from the money they contributed. The Citizens decision just made it a lot easier to have large contributions make a more direct impact on an election. Anyone interested in a more detailed explanation of how things worked before the Citizens case and how they work today should check out the New York Times magazine article of July 22, 2012 entitled “How much has Citizens United changed the Political game?”

Federal laws apply to political contributions for Federal office holders or candidates seeking Federal office.

The following restrictions on political fund-raising are established by Federal statutes:

..It is not lawful for one Federal official or employee to solicit or receive campaign funds from another Federal employee or official. Political solicitation by anyone in any Federal Building is unlawful.

..It is lawful for any official or employee to make a voluntary contribution to any political party that he may prefer. An employee cannot be forced to make a contribution, and must not be discriminated against for not doing so.”

Party finance is explained more fully in the chapter, titled “The Political Leader’s Problems.”

Federal, state and local laws almost universally restrict or outright prohibit the use of government employees from doing campaign work from their office or during their normal work hours. Many elected officials have been tripped up by the temptation to use employees for fund raising and other campaign activities.

But all is not gloom and doom and not all elections are going to be “purchased” by George Soros and the Koch Brothers. As hopefully the reader has observed, effective and long term commitment to organization at the precinct level and working upward can place moderate and responsible candidates on the ballot in primary and general elections and can, if the organization and commitment can be sustained, get moderate and responsible candidates elected at the local, state and national level. Conversely those individuals that get elected and then “fall off the rail:” can be successfully contested in the next primary election.

If every precinct was organized as this material provides a map for, and if reasonable people who have the best interest of all citizens in mind remain committed, the power of big money can be defeated. After all, the big money is just attempting to use advertising rather than organization to obtain votes. In many respects both parties have abandoned organization at the precinct level in favor of big advertising budgets.

Budget: The overall plan for expenditures during the campaign is developed by the policy groups and the treasurer.

The treasurer may be the regular party treasurer or they may be appointed just for the campaign.

The usual problem of preparing a realistic and workable budget is made more difficult in many campaigns because the treasurer must outline a spending program before they know how much money will be available. As a result, it is common practice to draw up a budget that anticipates various levels of income in advance of the campaign.

From a practical standpoint this means that a system of priorities will be worked out with provision made for essential expenses first. For example, rent for the headquarters office would have to be paid. But the decision as to whether one or two mailings of literature would be sent to voters would be determined by the success of the finance committee in raising funds.

Authority to make disbursements is generally limited to one person, the treasurer. They can be overruled only by the policy group.

Sometimes, members of the finance committee hold the view that the same committee should serve as a disbursing committee. Experience has shown that such a procedure invariably causes difficulties since the people who know how to raise money seldom know very much about how to spend it in a political campaign.

The importance of good accounting procedures can hardly be overemphasized. When prospective donors know campaign funds are audited by a certified public accountant, the problem of raising such funds is made easier.

One problem in raising campaign money is particularly important. Money generally comes in toward the end of the campaign. As a rule, donors do not get excited and loosen their purses until the campaign reaches its highest pitch. (This is unfortunate, since the earlier the money comes in, the more efficiently it can be spent.) Therefore, it is generally necessary to spend more than is available during the early—and often even the later—stages of the campaign.

This may seem like poor business methods, but it may be sound in politics. The winner of an election usually receives a number of checks from people who “just forgot” to send them in before Election Day. It is not good political sense to cut down on last-minute expenditures, since this may result in losing the election. The purpose of the campaign is to win, not to balance a set of books. Unfortunately the losers end up scrambling to cover their debts.

In elections where there is a significant interest at the State or National level the budget process will take into consideration what non-direct contributions from Political Action Committees and other organizations could have to take care of some of the expenditure requirements that would normally have to be undertaken by the finance committee. Care needs to be taken however, to avoid direct linkage to PAC funded activities and the activities of the campaign. A more detailed review of the linkage problem is contained in Chapter 8.

Election Day Elections are Still Won or Lost in the precincts. The careful selection of candidates, a well-organized campaign with publicity, television and radio advertisements, billboard advertising – all these have as their primary purpose in getting voters to the polls to vote for the party’s candidates. Money has somewhat obscured this truism but good candidates and well run campaigns supported by organized precinct activity will also win elections.

Any campaign is incomplete unless there is a big push, organized right down to the precincts, to get the individual

voters to the polls on Election Day.

Getting out the Voters:

This organized push revolves around three centers—the polling places; the precinct headquarters (usually the precinct leader’s home); and the central campaign headquarters for the community.

Usually several temporary committees are organized to handle Election Day affairs. They might be combined in one way or another, but the individual functions have to be performed by someone if the Election Day push is to be carried on properly.

There must be checks to see who votes; a telephone committee to remind the voters to vote; a baby sitting committee and a transportation committee. Although the election laws of the states may differ in details, in general two types of officials are present at polling places on Election Day.

One group is composed of the official inspectors and clerks. Although they may be selected from names submitted by political parties, these officials are paid by the local community or by the state, and have official duties to perform in determining that the voters are properly registered and in tallying the vote.

The poll watchers or challengers are certified by the parties and, if paid, are paid by the parties. They are present primarily to protect the interests of their party or candidate.

Practical politicians have learned that the selection of informed individuals as challengers who can be firm when

needed, and aggressive if the circumstances call for it, can pay dividends in close elections. It is recommended that a short training school be conducted where challengers are taught to recognize infractions of the voting laws, how to challenge voters and the procedures to be followed in handling challenges. Challengers may be challenging voters who may be in the Sinners classification. They may often be on the other side of a challenge and will be contesting the challenges of the opposite party.

Members of the legal committee should be standing by at the headquarters, or available by cell phone, if a voter of their party is challenged. An attorney should be prepared to go into action FAST and carry the matter to the Board of Elections that day.

Timing and Issues The goal of every campaign is to bring the enthusiasm of the workers and of the voters to its highest peak on Election Day. Almost everyone remembers campaigns in which the candidate seemed to be more popular at the beginning of the campaign than at the end. This may have been due to some unfortunate remark during the campaign that received wide publicity (such as the secretly recorded remarks of Mitt Romney about the 47%) but more likely it was due to the fact that the campaign peaked prior to Election Day. In other campaigns, it may have become obvious that the campaign drive was organized too late to achieve maximum effectiveness on Election Day.

Presidential election campaigns appear to unofficially start a year or more prior to Election Day. This trend of very early campaign starts has worked its way down to the state levels and many candidates for governor may be beginning their campaigns a year or more before elections.

This technique of starting campaigns long before – maybe a year or more – the formal announcement of the candidacy is becoming more prevalent. This has many advantages (and some disadvantages). It can be made to appear that the candidate is responding to a popular demand that they run. Favorable publicity may be easier to obtain when a popular person has not formally announced by speaking before many organizations. After they have announced the press and the voting public will probably be less willing to lend support to their remarks

At the same time practical politicians are building up their candidate they will use all possible techniques to deflate the opposition.

All of us have some memory of a particularly skillful response or reply that tended to damage the opposition beyond repair. The Republican’s use of actual (or allegedly actual) members of the Swift Boat units during the Vietnam War in response to John Kerry’s war record was something that Kerry never quite recovered from. During a presidential primary Pat Buchanan came up with the phrase “America First” and George H.W. Bush successfully countered that with the disclosure that Buchanan drove a foreign car. No one will forget the “Willie Horton” tag that got hung on Michael Dukakis after he made what appeared at the time to be a routine pardon for Mr. Horton who, proceeding upon leaving prison, to almost immediately commit more violent crimes.

Perhaps the greatest one of all was Lloyd Bentsen’s comments during a vice presidential debate with Senator Dan Quayle when he told Quale “you’re no Jack Kennedy”. Although Quale was only attempting to compare his time in the Senate to that of Jack Kennedy before he ran for President, Bentsen’s comment was picked up by every news outlet and Quale could never get out from under it. As a side note, it appeared to all who watched that debate that Bentsen’s comments were totally unscripted but Bentsen knew that Quayle had been using the reference to Kennedy’s short time in the Senate to counter complaints about his relative inexperience and Bentsen was determined to use it against him if it came up in the debate. And did so with a devastating effect.

“It has been said that “Political skill “is mostly built on proper timing.” By and large this sense of timing must be developed through trial and error in campaigns. At the same time, there are some useful guideposts—the most important of which is the official election calendar. This is based on the legal requirements for such things as the last day of absentee voters’ applications, the last day for submitting petitions for nomination in order to get on the ballot, the last day for registration and the last day for naming election officials and similar things. This timetable, of course, varies in different states.

The following possible timetable for a campaign will serve not only as a useful guide in planning a campaign, but also as a review of the entire campaign procedure.

Campaign Timetable

Primary Election In most states, the campaign for the general election is preceded by a primary election in which the parties nominate their candidates. Primaries may be held anytime from January on, as specified by state law. Primary campaigns may be just as thoroughly planned and organized as a regular election campaign. They usually differ in that:

The campaign organization must be built more or less “from scratch” without help from the regular organization.

A personal precinct organization must be built.

Funds are often more difficult to come by for a person in a primary than for a party in a general election.

Petitions must be circulated to get on the primary ballot.

All suggested dates may have to be changed to meet the demands of a specific race.

General Election This timetable can apply to a party organization campaign effort or the effort of a major candidate. Obviously selection of certain chairmen will be unnecessary if a candidate’s primary campaign organization is carried over into the election campaign. Between Primary and September 1st.

.Decisions are made between party organization and winning primary candidates on the extent to which individual campaigns should be integrated with campaign for whole ticket. Individual candidates will gear their platform to the party platform.

. The campaign manager, publicity director and finance chairman are

selected

. Plans drawn up for the campaign. Decisions are made on what the party organization will do, what financial and other help can be expected from local or national PAC’s, and what campaign committees of the individual candidates will do.

. The Budget is drawn up and funds allotted among party organization and candidates.

. The fundraising drive is started.

. A research committee is appointed and put into high gear immediately. Candidates should complete education on all aspects of campaign and speech writing is commenced.

. Issues and campaign strategy are worked out. Campaign literature including posters and billboards is completed.

. Campaign headquarters are opened, furnished including computers, printers, copy machines and phone banks. A headquarters secretary is obtained and volunteer chairman selected

. Recruiting is begun. Remaining campaign committee chairpersons are selected.

. A good map for headquarters is obtained along with detail maps for each precinct and distribute to precinct leaders.

. Vacant precinct leadership positions are filled. Precinct leader’s start building up their precinct organization in preparation for registration. Registration lists and street-by- street listings are prepared for distribution to precinct leaders.

.Auxiliary campaign groups such as “Citizens for Whoosit,” and special groups such as “Veterans for Whoosit,”

“Farmers for Whoosit” are arranged for.

. Speakers program is started and speakers are trained and briefed. Scheduling speaking engagements before key organizations is started. September 1st. To September 30: Operations get under Way.

. Start the publicity program; time it to reach peak during last ten days of campaign; coordinate activities of research and publicity; plan situations for a story-a-day and a picture-a- day for distribution from October 10 to Election Day.

. Get basic literature to printer. (Should be ready in early September.) Print one good piece of affirmative literature, setting forth the candidate’s qualifications; use good paper; make it a masterpiece; instruct the printer to hold the master copy for possible additional printing.